Two years ago today, we lost our Audrey, just days after finding out she had cancer. I held her and sobbed on the floor of the vet’s office, reeling from the shock. The tumor was under and through her tongue. Completely inoperable, and getting bigger by the day.

We’d adopted Audrey from our local city shelter eight years and five months earlier. She was a skinny, meek little puppy, who kissed our Bogie obsessively under his chin when they first met. We took her home and loved her, sitting on a stump in our backyard, going through the names of all the actresses who had ever been in movies with Humphrey Bogart, as she explored her new life.

The day after we adopted her, she began vomiting. The emergency vet sent her home after what turned out to be a false negative parvo test. She got sicker and we ended up at another emergency vet, where she stayed for a week. We were able to visit her, but we had to wear gowns and gloves, holding her little bony frame, IV tubing running from her little front leg. Parvo is a rollercoaster. Puppies often get better, only to crash again, but our girl prevailed, despite developing double pneumonia and finally, we were able to bring her home.

At night, she slept under the covers. She was so terribly thin, it was physically and emotionally painful to hold her. She licked herself to sleep each night, as she would for the rest of her life, coughing occasionally from somewhere in the crook of our knees. Soon afterwards, with her compromised immune system, she developed demodectic mange. Once she recovered, we had her spayed and returning to the vet to have her stitches removed, she stepped on glass in the parking lot and had to have general anesthesia to have the gaping wound in her paw stitched. Then she ate an unknown amount of prescription medication. We took to calling her our “money pit,” but we said it with much tenderness.

We knew how important socialization was to a puppy of her age, but we had to keep her isolated from other dogs for weeks while she continued to shed parvo. We played socialization CDs of babies crying and loud noises and we hoped that her interactions with Bogie, who had just been titered for parvo immunity, would be enough to keep her dog social.

But as she grew, her behavior around dogs left much to be desired. She twisted and howled at the end of the leash when she saw another dog, she got into a handful of dog fights, which were loud and scary, though she never hurt the other dog. She would even jump aggressively onto our Bogie, barking, if the door bell rang. She loved Bogie, though she bullied him. She loved my parents’ dog, and looking back, I think she would have loved puppies. She had a hard time relaxing when we took her places, and that combined with our embarrassment over her antics, our fear of giving pit bulls an even worse reputation since people didn’t know this dog sounding like a banshee on the end of the leash had never hurt a dog, these things made us leave her at home much more than we should have. She deserved better.

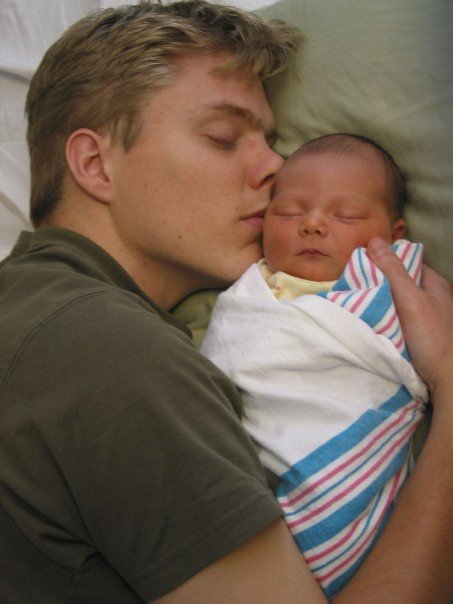

But oh, her love of people was powerful, and babies and children in particular. She would sneak around behind anyone holding a baby, not giving up until she’d been able to lick little toes. She was tolerant and patient with children. When a little girl tried to jump over her as she lay sleeping in the shade of a stiflingly hot summer day, and instead came down on Audrey’s ribcage with her full weight, Audrey got up and moved. No growl, no reprimand. When our third baby was born at home, our midwife arrived a little apprehensive about pit bulls. Three hours later, after our son’s birth, she held him out for Audrey to lick, to welcome. Oh, how she loved my babies, her babies.

It was hard having Audrey. It was hard not being able to go on vacation without her making herself sick in our absence. It was hard having a dog so upset about being left alone that she put her paw through our bedroom window and then wagged happily all the way to the vet, gushing blood, but happy to be going along. It was hard not being able to take her places comfortably, and it was hardest of all that people thought she was dangerous when she was so far from it. And oh, it was hard to lose her, at eight, as we had lost Bogie.Our sweet vet came to our house, our friends arrived to take care of the kids, another friend brought Audrey chocolate ice cream. We’d walked with her in the park, let her off the leash to chase squirrels that morning. She was still so completely healthy and full of life everywhere except for that tumor, that growing tumor that made it hard for her to eat. Painful for her to drink. And we thought of Bogie, and of how much he had suffered, and we were relieved that there was no choice for us, relieved there was no chance to fight it because we feared fighting it too long again.

And Mia was too sad to stay at school and came home one more time to say goodbye to her, as we held her in our front yard, and after she had left with our friends, the vet gave Audrey a sedative. She gave her a sedative because she was still so alive and vibrant. And Audrey struggled against it for a moment, surprised, as she collapsed in my lap, and we held her and cried. And I remembered regretting how desperate my “I love yous” had sounded at the end with Bogie. And I wanted to be stronger for our girl. So I steadied my voice, slowed my words, and I held her, as she went limp in our arms, I held her and whispered, “Thank you. Thank you for being such a good mama to my babies.”